- Home

- Collections

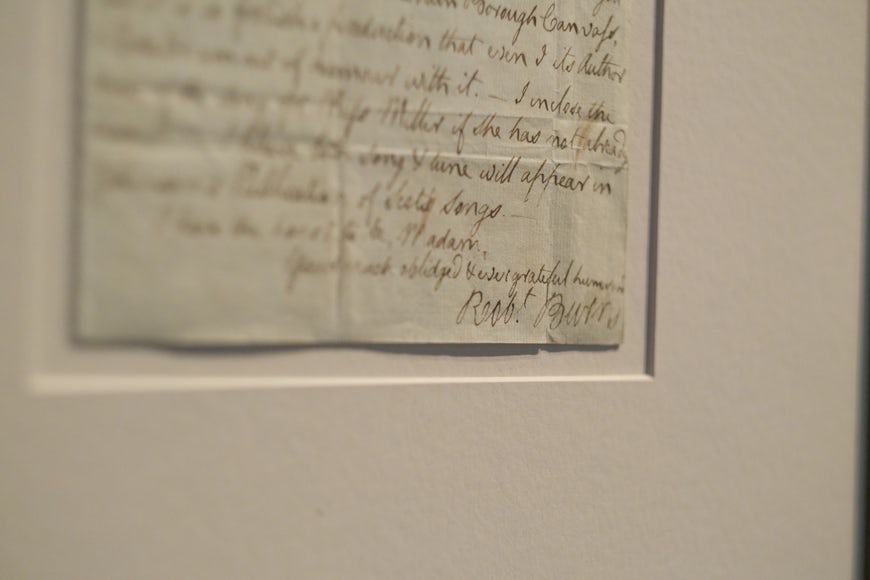

- Robert Burns Collection

- Burns and Georgian print culture

Burns and Georgian print culture

Written by Dr Craig Lamont, University of Glasgow

Robert Burns published his debut collection of poetry, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, in the summer of 1786. The printer was John Wilson, from Kilmarnock, and the book is often referred to simply as the ‘Kilmarnock Edition’ or the ‘Kilmarnock Burns’. Wilson printed 612 copies and it contains some of Burns’s most famous works, such as ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’, ‘To a Mouse’ and ‘The Holy Fair’. The book was dedicated to Gavin Hamilton (1751–1805), a lawyer and close friend of Burns. Hamilton advised Burns about the printing venture to begin with, partly to help him raise the funds for his planned trip to Jamaica to be a book-keeper on a plantation worked by enslaved labourers. Despite booking three tickets to make the journey across the Atlantic, Burns was hedging his bets. The positive reception of the Kilmarnock Edition created the enticing prospect of further literary success in Scotland and in the end, Burns let the opportunity in Jamaica sail by.

In December 1786, a review of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect was published by Henry Mackenzie (1745–1831), the author of The Man of Feeling (1771). In this positive review, Burns was described as ‘this Heaven-taught ploughman’, which remains today as a romanticised image of Burns but in some ways distracts us from just how well-educated he was. The importance of the Kilmarnock Edition lies not just in the poems themselves, but also in what Burns said about poetry in the introduction to his own book. He wrote that he did not have ‘all the advantages of learned art’ given to most poets, and that he was ‘unacquainted’ with the rules on how to become an established writer. Instead, he chose to focus, using Scots, on his surroundings and the manners and feelings of everyday life. But he also cited classical poets like Virgil, and two great predecessors in Scots poetry: Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) and Robert Fergusson (1750–74). In other words, Burns knew his poetry well, but he played into the image of the ‘ploughman poet’ in order to further his literary career.

Following in the footsteps of Ramsay and Fergusson was one thing in establishing a ‘Scots’ poet, but Burns was also working in the afterglow of some of the brightest moments of the Scottish Enlightenment. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, published in London in 1776, was among the many Scottish works to inspire Burns. Burns’s famous lines ‘O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us/ To see oursels as others see us!’ echoes Smith in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759): ‘if we saw ourselves in the light in which others see us, or in which they would see us if they knew all, a reformation would generally be unavoidable.’ Scottish philosophers of the Enlightenment were working in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and London at this time. And it was in Edinburgh, the most celebrated metropolis of the Scottish Enlightenment, where Burns’s success was firmly established.

On 14 December 1786, William Creech (1745–1815) published the proposals for printing a second edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. Creech was a bookseller and magistrate, involved in publishing works by the minister Hugh Blair (1718–1800) as well as Robert Fergusson. Given the success of Burns’s first edition, Creech agreed to produce around 1,500 copies of Burns’s new Poems. The subscription list grew rapidly, and by March 1787 around 3,000 copies had been produced, with more on the way. In a letter to his friend and supporter Frances Dunlop (1730–1815), Burns said: ‘I have both a second and a third Edition going on as the second was begun with too small a number of copies.’ At this point, there were hundreds of small errors made in the printing of the new copies, including the famous misprint of the word ‘skinking’ as ‘stinking’ in ‘Address to a Haggis’. Following the great success of Burns’s Edinburgh book, Strahan and Cadell – the same publishers of Smith’s Wealth of Nations – produced a London edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. In the same year, an unauthorised Irish edition was produced in Belfast and Dublin, and by 1788 there were editions printed in Philadelphia and New York.

It was not only Burns being recognised for his talents at home and across the Atlantic; his contemporaries were also benefitting from his fame. In the Kilmarnock Edition, Burns wrote the ‘Epistle to Davie, A Brother Poet’, for his friend David Sillar (1760–1830). Burns’s success meant that Scots poetry became more desirable, and in 1789 Sillar printed his own Poems, with the same John Wilson of Kilmarnock who had published Burns three years before. The book opens with an endorsement of Sillar by Burns.

But despite all this, writing in his native Scots was not unanimously celebrated. One of Burns’s renowned friends was Dr John Moore (1729–1802), the physician and novelist to whom Burns sent his detailed autobiographical letter on 2 August 1787. Moore was highly encouraging of Burns, but he did suggest writing more in English and less in Scots, in order to appeal to more readers. As we know, Burns took this advice with a pinch of salt, and continued to popularise Scots poetry and song throughout his life.

After his death, Burns became incredibly popular in both Glasgow and Edinburgh, with new editions of his poems appearing in the ensuing years. A new edition was also published in Philadelphia in 1798, based on ‘the latest European Edition’. Pamphlets and poetry anthologies used Burns’s verse to help sell cheaper editions, and many lesser-known poets contributed in the style of Burns. In 1800, four years after Burns’s death, the first collected Works of Robert Burns was produced, consisting of four volumes. Other multi-volume works soon appeared, each with its own focus on Burns’s life, relationships, character and talents. Many liberties with the truth were taken at various stages of Burns’s posthumous career, but the essence of the great writer and song-collector is indelible, and his legacy remains rich to this day.