- Home

- Collections

- Robert Burns Collection

- Witchcraft and Burns: Reality and rhyme

Witchcraft and Burns: Reality and rhyme

Written by Zoe Venditozzi, novelist and host of Witches of Scotland podcast

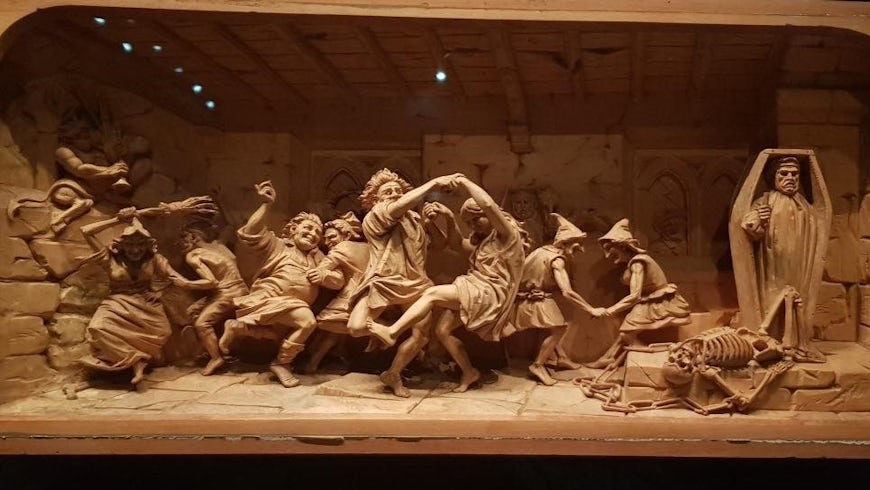

Alongside Shakespeare’s Macbeth, one of the most famous fictional representations of witches is surely Robert Burns’s Tam o’ Shanter, an epic narrative poem about witchcraft and ghouls. For many in Scotland, Tam o’ Shanter is the embodiment of witchcraft and the occult, and the poem is still widely recited, studied and referenced, particularly around Halloween. The mixture of sexual allure and terror, inspired by the wild, half-naked dancing of Nannie and the other witches, helped to perpetuate stereotypical depictions of Scotland’s ‘witches’ that were far removed from the realities of those accused of witchcraft just a few decades earlier. Straddling folk stories and reality, the poem builds upon the lingering popular fears and beliefs about women’s role in witchcraft.

Witchcraft in Scotland

Burns was born just 23 years after the repeal of the Witchcraft Act in 1736 and it’s likely that tales from those days were still in circulation. The Witchcraft Act was brought into law in 1563 in Scotland. During its time on the law books, approximately 4,000 people were accused and more than 2,500 were executed. Of those, 84% were women. Reflecting today on the social and religious forces driving an overwhelmingly Christian country into genuinely believing in the existence of the Devil and his use of humans – mostly women – to do his evil bidding on Earth in the form of witches seems alien and unbelievable. But, a huge struggle for power was being fought and ultimately thousands of people paid the price in those paranoid and insecure times.

When people were accused of witchcraft, they were generally taken into custody by the minister and local officials, before being questioned and examined. Initially, people were physically tortured using pilliewinks [thumbscrews], ropes around the throat, and various other barbaric means. Over time, the legal system decreed that physical torture must cease, and the questioning changed to using the watch-and-wake technique where the accused were kept awake for days and even weeks until providing a ‘confession’. Nowadays, we recognise sleep deprivation as torture; studies have proven that beyond a certain point people will speak against their own best interests to make it stop. This is precisely what happened during the witch trials in Scotland. Once a ‘confession’ was secured, the accused was executed. Usually, they were hanged and then their bodies were burnt. This achieved several ends: one, a public spectacle that both entertained and educated through terror; two, the ‘witch’ was denied a Christian burial; and three, the ‘witch’ could not ‘revenir’ (return from the dead), having been reanimated by the Devil.

Burns was born exactly 100 years after the infamous Dumfries trial where Judges Mosley and Lawrence presided over the three-day trial of 10 local women in 1659. Whilst Helen Tait’s accusation was found not proven, the other women – Agnes Comenes, Janet McGowane, Jean Thomson, Margaret Clerk, Janet McKendrig, Agnes Clerk, Janet Corsane, Helen Moorhead and Janet Callon – were found guilty and sentenced to execution on Wednesday 13 April 1659. 50 years after this group execution, what is described as ‘the last trial for witchcraft by the Court of Justiciary in Scotland’ occurred in 1709, where Elizabeth Rule was condemned to be branded on the cheek with a red-hot iron. Supposedly, witnesses at the time described smoke coming out of the poor woman’s mouth. This event would likely still have been spoken of during Burns’s lifetime and may have had some influence on his storytelling.

Burns, Tam and witchcraft

Whilst Burns was a man of the Scottish Enlightenment, he still used certain elements of traditional Scottish mythology in his work, deployed to such dramatic effect in Tam o’ Shanter. Alongside his classical education, Burns received a thorough grounding in the ancient tales and folklore of Scotland from his mother, Agnes Broun. You can see the weaving together of these two distinct threads in Tam o’ Shanter. The narrative poem was written in 1790 and published in 1791 at the request of an antiquarian called Francis Grose. Burns provided three ‘witch stories’ associated with Alloway Kirk, the second of which was Tam o’ Shanter.

Burns’s autobiographical letter written to Dr John Moore in 1787 highlights how the superstitions of Betty Davidson, Agnes’s maid, also had a huge influence on his creative works. Burns wrote, ‘In my infant and boyish days too, I owed much to an old maid of my mother’s, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity and superstition. She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the county of tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, enchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery. This cultivated the latent seeds of Poesy; but had so strong effect on my imagination, that to this hour, in my nocturnal rambles, I sometimes keep a sharp look-out in suspicious places; and though nobody can be more sceptical in these matters than I, yet it often takes an effort of Philosophy to shake off these idle terrors.’

This hyper-awareness of ‘suspicious places’ is of course reminiscent of Tam’s journey towards Alloway Kirk when he recalls locations where murdered people were found, setting the scene for the dark delights of the unnatural ceilidh he is about to spy on.

Witches of Scotland campaign

There’s a saying that those who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it, and never has that been clearer than now. This idea of understanding the past to live better lives is what drives the Witches of Scotland campaign. Since we started the campaign in 2020, we’ve been overwhelmed by the interest and support shown by people, not only in Scotland but worldwide.